The Dividing Line Between Introverts and Extroverts Isn’t So Clear

Introverts and Extroverts are less different and more alike (Pt. 3)

Think of the stereotypical introvert and extrovert, and keep that image in your mind. What comes to mind for the extrovert? Being the life of the party, the social butterfly in the office? Constantly going out? What about the introvert? Being a homebody? Always shy and quiet? At home, binging some anime or gaming?

As stated earlier in this series, introversion and extroversion don't describe two different types of people. They indicate where people lie on a spectrum. The above characterisations, at most, represent the extremes of the distribution. In reality, not all extroverts are highly extroverted, and not all introverts are deeply introverted.

Given this divide, how extroverted does one have to be to be labelled an extrovert and vice versa? After discussing the definition of extraversion and the biological theories behind it, we are now equipped to answer these two questions: How do psychologists measure extraversion? And how different are introverts and extroverts?

*Please note the slight inconsistency between "extroversion" and "extraversion." "Extraversion" is the psychological term; individuals high in this trait are labelled "extroverts/extraverts", and those lower labelled "introverts."

The Problem with Measurements in Psychology

Due to my engineering background, navigating the psychological literature has been one of the most frustrating experiences of my life — this was most evident in the field of measurement. In the social sciences, few concepts or measures are definitive, even when dealing with its most fundamental constructs, like personality traits. An excerpt from Gregory T. Smith encapsulates this:

Physical science has an International Bureau of Weights and Measures with, for example, a bar reflecting the true length of a meter. Measuring length, for physicists, has an agreed-on, concrete anchor. Psychology has no such thing. We infer the existence of traits such as neuroticism because doing so has obvious utility for describing persons, their differences from each other, and the nature of dysfunction.

These limitations understandably raise doubts about the precision of many psychological findings, and I share this scepticism but have some sympathy. Psychology faces unique difficulties among the sciences, primarily because of the complexity and constraints involved in recording people’s internal experiences. Being held back by ethics hampers these efforts even more.

Despite these obstacles, I respect the pragmatic approach psychologists take. Much like engineers, they often must make practical compromises. So yes, personality traits are postulated or inferred rather than theoretically derived. However, contrary to the critiques levelled at psychology, I think the field's personality frameworks are society’s most practical and thoroughly tested ideas. I value them for their descriptive rather than predictive power. Given these necessary compromises and considerations, let’s investigate how personality traits have been measured.

Brief Overview of Measurement Methods

Self-report assessments—like those entertaining quizzes that identify your House in Game of Thrones or Friends character—are widely used in psychology, though professionally, they're far more detailed and rigorously developed.

Self-reports are popular because they're straightforward, efficient, and standardised, allowing researchers to quickly collect and compare large amounts of consistent data across diverse populations. However, the assessment is limited by self-bias. The accuracy of the test depends on how self-aware and honest the person is with themselves when answering.

Informant reports address self-report biases by gathering perspectives from friends, family, or coworkers who directly observe the participant’s behaviour. However, these observers may also introduce biases due to personal relationships.

Behavioural observations give a more objective insight by examining individuals directly in accurate or controlled settings, but this approach is time-consuming, costly, and still vulnerable to observer bias. Researchers sometimes combine the above with other methods like behavioural sampling, social media analysis, or longitudinal studies to achieve a more multifaceted personality assessment.

Today, self-report assessments remain the most widely used tool in measuring personality. Thus, the field of psychology has developed this method the most.

Brief History of Personality Assessments

At first, personality assessments focused on diagnosing only the negative aspects of personality. This began with Robert S. Woodworth's Personal Data Sheet, which aimed at identifying soldiers susceptible to "shell shock" (PTSD) during World War I. Similarly, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) was created to diagnose psychopathology in clinical settings.

Then, as comprehensive personality theories began to pop up, an effort to quantify their measured domains began. Two pioneering models were Cattell’s Personality Factor Test and Eysenck's Personality Questionnaire (EPQ). Cattell’s model measured up to sixteen facets, while Eysenck’s only measured three: extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism.

A monumental shift occurred with the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), which popularised measuring the Big Five traits—Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. Later tools, like the Big Five Inventory (BFI) and the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP), continued refining personality assessments based on the Big Five framework.

Tests like the BFI include 44 phrases rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The NEO-PI-R has 240 questions using the same scale. Meanwhile, the EPQ uses 100 yes/no questions. Responses from these are converted into numeric scores for analysis. Let's explore their results!

What are the Results?

Carefully examine the plots below based on some of the questionnaires above, noting patterns in how and where scores tend to cluster.

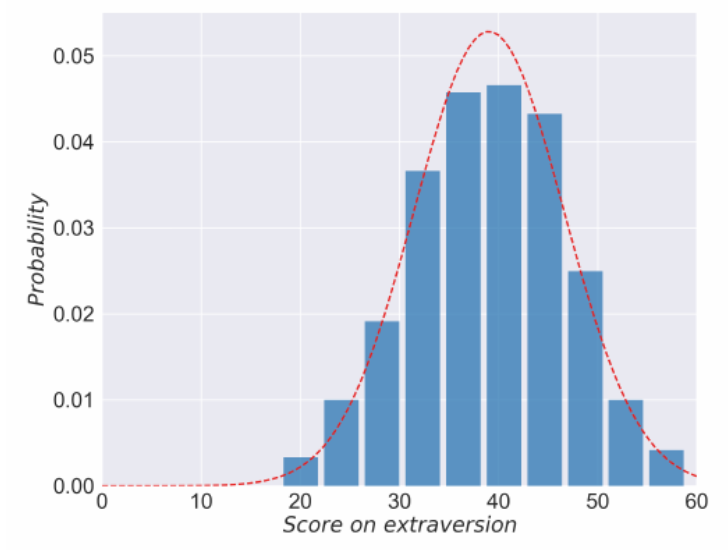

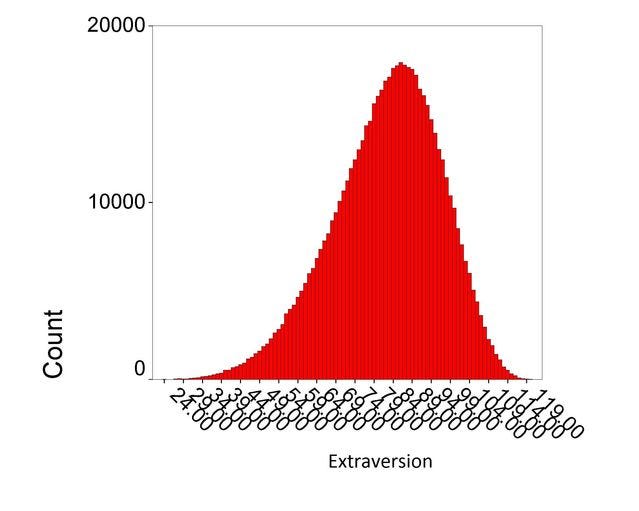

Across these and other studies, extraversion consistently emerged as a normal distribution, sometimes with a rightward skew. This means most individuals cluster near an average level of extraversion, with progressively fewer people appearing at either extremes of being highly introverted or extroverted.

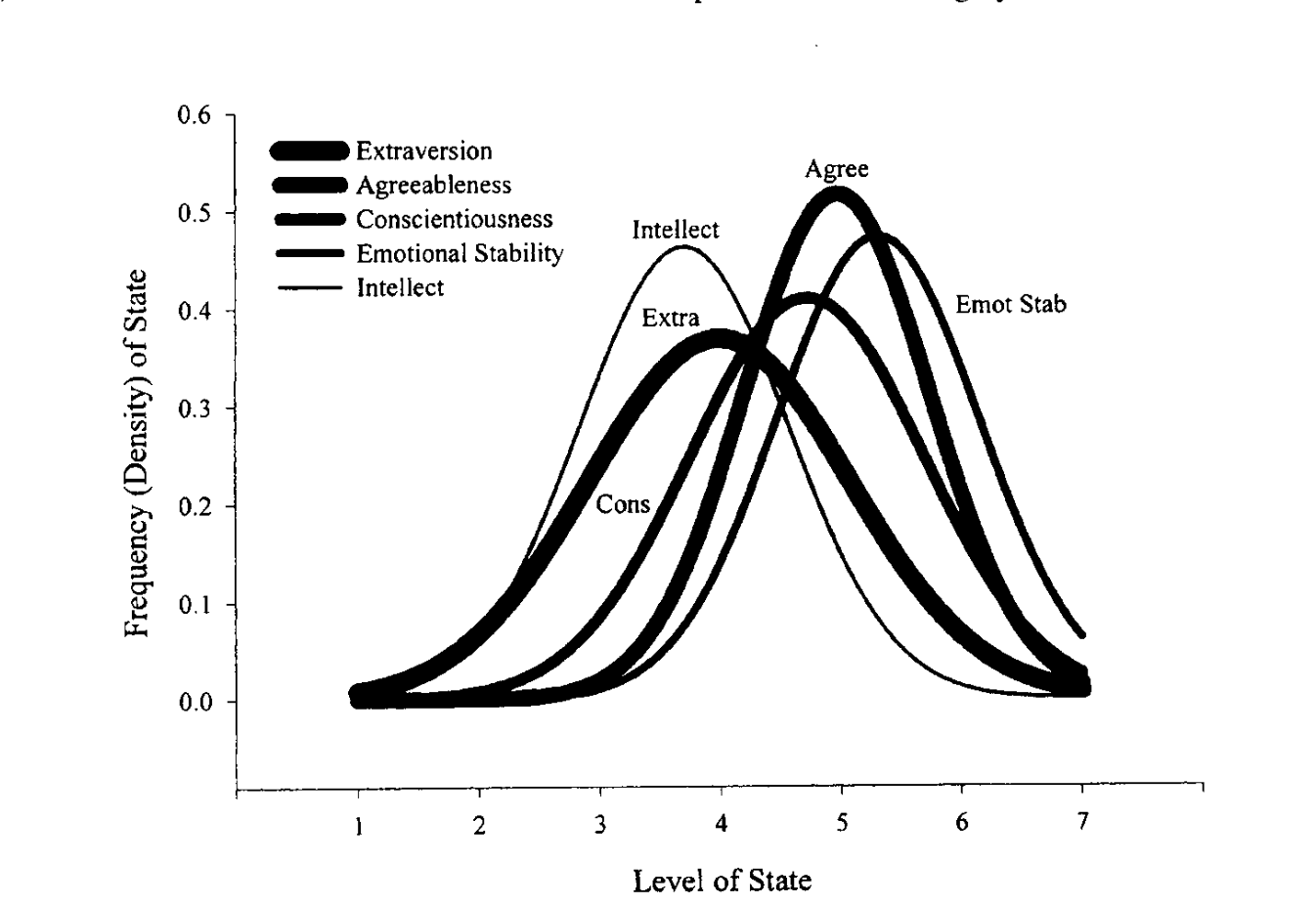

This intuitively makes sense. Like other continuous scales of physical human measures like height and weight, fewer people are at the extremes, and most are in the middle. Why wouldn’t this apply to mental human measures, too? However, this is not true for all personality traits. Observe the plots below, but again, pay attention mainly to extraversion.

Unlike agreeableness, we can observe that extraversion still fits into normal distributions, but these results are not always static or consistent. Some studies I came across found that the distribution of extraversion differed with age and gender. In addition, one of the most extensive surveys on extraversion using the NEO-PI-R across multiple countries showed that each country’s extraversion scores had different means and standard deviations. However, the distributions still tended towards normality.

I ascribe these differences to societal or cultural differences between sample groups. Interestingly, when I plotted each NEO-PI-R’s sample group mean, it showed an approximately normal distribution. These results suggest that there is likely a normal distribution between, within countries and globally.

Overwhelmingly, most studies I found showed a normal distribution with a slight skew towards higher extraversion scores. Given the number of samples and the consistency of these distributions, psychologists must have created a consistent empirical distinction between introverts and extroverts right? RiGHt?? RIGHT????

Psychology is just vibes, guys, I promise. I'm just kidding, but the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator definitely is. When we hear statistics like "30-50% of people are introverts," such categorisations can be misleading. These percentages are arbitrary cut-off points along this continuous distribution.

Even in academia, the dividing line between introverts and extroverts currently seems to be left up to the eye of the beholder; I found no universal limits. Some assessments specify one but do not share their rationale. When referring to introverts and extroverts, most papers generally refer to those who are higher or lower on the scale.

In an article, John A. Johnson, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, describes the difficulty of categorising people as introverts or extroverts in the field. He joins my bemusement that there are no universal breakpoints between the groups.

In his study of nearly 620,000 people (see red distribution plot earlier), he explained that psychologists typically use a half-standard deviation rule (classifying ±0.5 SD from the mean as "average," resulting in roughly 30% introverts, 40% average, and 30% extroverts) or one complete standard deviation rule (classifying ±1 SD as "average," resulting in about 68% average and 16% each to the two camps).

However, Johnson's research found that the commonly used half-standard deviation rule correctly classified only 41% of cases compared to acquaintance ratings. This highlights the subjectivity involved in personality categorisation.

I imagined that regardless of the distinction used, those on the extreme left and right had to be significantly different from each other. Luckily, I didn’t have to rest on my imagination. A 2010 paper published in the National Library of Medicine was researching just that!

Fleeson et al. conducted a meta-analysis of 15 experience-sampling studies over eight years, collecting over 20,000 reports of trait expressions in behaviour. Their methodology involved having participants complete the BFI questionnaire and then report on their actual behaviour multiple times per day for several days as it occurred naturally.

The results showed that while introverts (-1 Std dev below the mean of the questionnaire) and extroverts (+1 Std dev above the mean of the questionnaire) do differ in their average behavioural tendencies, there is substantial overlap in how they behave in daily life (see below image).

The researchers found that introverts regularly act extroverted, and extroverts regularly act introverted. Specifically, extroverts acted in moderately extroverted states about 5-10% more often than introverts, and introverts acted in moderately introverted states about 5-10% more often than extroverts. This overlap was not as applicable to other personality traits.

From an engineering perspective, I recognise the practical utility of examining phenomena through contrasting extremes. For instance, in my fluid mechanics class, we learned to apply different equations depending on whether the fluid was in calm, predictable conditions (laminar), more chaotic, unpredictable ones (turbulent) or in transition.

We calculated a critical value—the Reynolds number- to determine the flow regime—based on objective measures like fluid velocity, density, and viscosity. Unlike physical systems, human behaviour does not neatly align with such clearly defined boundaries.

There is also a philosophical discussion to consider: what is the value of a measure if it cannot meaningfully distinguish between two groups? Does a measure fail if it cannot clearly delineate categories? I think not. While differences may exist, they should not be overstated. Extraversion is better viewed through the lens of probability—the more extroverted one is, the more likely they are to exhibit extroverted responses, and vice versa.

The majority of psychological literature on extraversion emphasises the two extremes—highly extroverted versus highly introverted individuals— this overlooks the reality that most people naturally fall closer to the midpoint, creating significant overlap between these two groups. Fortunately, the field has addressed this gap through the concept of ambiversion.

What is Ambiversion?

Ambiversion emerged as an alternative to Carl Jung's binary introversion-extroversion classification. In 1926, psychologist Heidbreder introduced a more nuanced perspective, suggesting that introversion and extroversion represent opposite ends of a continuous spectrum, with many individuals naturally falling somewhere in between.

Ambiversion refers to this middle ground—individuals who display both introverted and extroverted tendencies depending on the context. This concept aligns with statistical findings showing that most people do not sit at the extremes of the spectrum. However, defining ambiversion presents certain challenges, as the boundaries distinguishing it from introversion and extroversion are often subjective. Some critics argue that incorporating ambiversion into personality frameworks may complicate assessment and reduce the clarity of quick, practical evaluations.

Despite these criticisms, research by Adam Grant, an organisational psychologist, found practical advantages of ambiversion, particularly in professional settings. Grant found that ambiverted salespeople significantly outperformed their introverted and extroverted peers. In the study, peak productivity was observed precisely at the midpoint of the introversion-extroversion scale. The study made the rounds in the blog and business community, with many embracing the unconventional findings and a new psychological group.

The problem with this new paradigm is that, like the introvert-extrovert debate, this new "ambivert ideal" could inadvertently fuel another division. It creates pressure to achieve a perceived balance or adaptability that might not reflect individual differences. It’s like we’re entering a new fighter in the introvert-extrovert arena, which I think we are tired of now.

Let's move beyond these labels. Identifying too closely with any of the previously mentioned groups has advantages and disadvantages. Gaining deeper self-awareness about your position on this spectrum can help you leverage your strengths effectively. However, identifying too deeply with a label might also limit your potential by narrowing what you believe you're capable of.

Ultimately, I believe we can live and pursue happiness or success regardless of where we fall on the introversion-ambiversion-extroversion spectrum. I’m optimistic about this because of a compelling idea I saw in a viral TED Talk and a popular book (Quiet: The Power of Introvert). This concept is called Free Trait Theory (this is the last psychological term I'll introduce here—I promise!).

Free Trait Theory

Brian Little's free trait theory posits that individuals can adopt "free traits," enabling them to act in ways that may diverge from their innate dispositions to advance personally significant projects. For instance, a more introverted person might exhibit extraverted behaviours to achieve a meaningful goal.

Although this adaptability can boost well-being by supporting goal achievement, it can also cause stress if individuals don’t recharge in their natural temperament. This perspective suggests that personality traits are not rigid constraints but can be flexibly expressed in alignment with one's core pursuits.

With this in mind, I have only one directive—don’t become fixated on the labels. Focus on understanding yourself and defining your aspirations. Rather than taking pride in inherited labels, invest effort into pursuits that bring you personal satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment. Strive to achieve goals that are meaningful to you and reflect the person you aim to be.

Ultimately, the most fulfilling label will be the one that signifies your authentic self.

Papers

[1] Smith, Gregory T. “On Construct Validity: Issues of Method and Measurement.” Psychological Assessment, vol. 17, no. 4, Dec. 2005, pp. 396–408, https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.396. Accessed 16 Mar. 2019.

[2] Gibby, Robert E, and Michael J Zickar. “A History of the Early Days of Personality Testing in American Industry: An Obsession with Adjustment.” History of Psychology, vol. 11, no. 3, 2008, pp. 164–184, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013041.

[3] Kim, Hyunji, et al. “Self–Other Agreement in Personality Reports: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Self- and Informant-Report Means.” Psychological Science, vol. 30, no. 1, 27 Nov. 2018, pp. 129–138, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618810000.

[4] Zhou, Zhenkun, et al. “Extroverts Tweet Differently from Introverts in Weibo.” EPJ Data Science, vol. 7, no. 1, 3 July 2018, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-018-0146-8. Accessed 19 Dec. 2020.

[5] Fleeson, William, and Patrick Gallagher. “The Implications of Big Five Standing for the Distribution of Trait Manifestation in Behavior: Fifteen Experience-Sampling Studies and a Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 97, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1097–1114, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016786. Accessed 19 Nov. 2019.

[6] Allik, Jüri, et al. “Mean Profiles of the NEO Personality Inventory.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 48, no. 3, 12 Feb. 2017, pp. 402–420, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117692100.

[7] Fleeson, William. “Toward a Structure- and Process-Integrated View of Personality: Traits as Density Distributions of States.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 80, no. 6, 2001, pp. 1011–1027, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.1011.

[8] Ramon, Yanou, et al. “Explainable AI for Psychological Profiling from Digital Footprints: A Case Study of Big Five Personality Predictions from Spending Data.” Information, vol. 12, no. 12, 13 Dec. 2021, p. 518, https://doi.org/10.3390/info12120518.

[9] Johnson, John A. “Measuring Thirty Facets of the Five Factor Model with a 120-Item Public Domain Inventory: Development of the IPIP-NEO-120.” Journal of Research in Personality, vol. 51, Aug. 2014, pp. 78–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.05.003.

[10] Stromberg, Joseph, and Estelle Caswell. “Why the Myers-Briggs Test Is Totally Meaningless.” Vox, 15 July 2014, www.vox.com/2014/7/15/5881947/myers-briggs-personality-test-meaningless.

[11] Saldana, Manuel, et al. “The Reynolds Number: A Journey from Its Origin to Modern Applications.” Fluids, vol. 9, no. 12, 16 Dec. 2024, pp. 299–299, www.mdpi.com/2311-5521/9/12/299, https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids9120299.

[12] Cohen, Donald, and James P. Schmidt. “Ambiversion: Characteristics of Midrange Responders on the Introversion-Extraversion Continuum.” Journal of Personality Assessment, vol. 43, no. 5, Oct. 1979, pp. 514–516, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4305_14. Accessed 21 Nov. 2019.

[13] Little, Brian R. “Free Traits, Personal Projects and Idio-Tapes: Three Tiers for Personality Psychology.” Psychological Inquiry, vol. 7, no. 4, Oct. 1996, pp. 340–344, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0704_6. Accessed 20 Jan. 2020.

[14] Little, Brian R. “Personal Projects and Free Traits: Personality and Motivation Reconsidered.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 2, no. 3, May 2008, pp. 1235–1254, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00106.x.

[15] Grant, Adam M. “Rethinking the Extraverted Sales Ideal.” Psychological Science, vol. 24, no. 6, 8 Apr. 2013, pp. 1024–1030, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612463706.

Books

Cain, Susan. Quiet : The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. New York, Broadway Books, An Imprint Of The Crown Publishing Group, A Division Of Random House, Cop, 2013.

Articles

Ambiversion

Extrovert or Introvert: Most People Are Actually Ambiverts from scientificamerican.com

There Is No Such Thing as an Introvert or Extrovert from psychologytoday.com

The Majority of People Are Not Introverts or Extroverts from psychologytoday.com

Why Almost No One Is 100 Percent Extraverted or Introverted from psychologytoday.com

Are You an Extravert, Introvert, or Ambivert? from psychologytoday.com

Why Ambiverts are better Leaders from bbc.com

Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that. from nationalgeographic.com

Are We Wrong About Introverts Vs. Extroverts? from refinery29.com

You’re Probably Not an Introvert (or an Extrovert) from humanparts.medium.com

Introvert, extrovert…or ambivert? from medium.com/@elena.karvouni20

Introverts, Extroverts, and the Majority in the Middle from pcma.org

On Ambiverts: Why Distinguishing Between Extroverts and Introverts is Inadequate from diplateevo.com

Ambivert: The Little-Known Personality You Need to Know About from themightymarketer.com

How Being an Ambivert Can Skyrocket Freelance Success from themightymarketer.com

Personality assessment

How Are Personality Traits Distributed in the Most Popular Personality Frameworks? from spencergreenberg.com

Types of Personality Tests from verywellmind.com

10 Best Personality Assessments & Inventories from positivepsychology.com

Measuring Personality from vaia.com

How are personality traits distributed in the most popular personality frameworks? from spencergreenberg.com

How Do Psychologists Determine Personality Trait Levels? from psychologytoday.com/

Videos

Measuring Personality: Crash Course Psychology #22 via CrashCourse

Personality Research Methods via Society for Personality and Social Psychology

Personality 1 by Jill Seiver via Jill Seiver

Who are you, really? The puzzle of personality | Brian Little | TED via TED